Making a cockpit canopy. Using scrap materials in aircraft modeling Making transparent cockpits for a model airplane

Various online stores are now, one might say, overwhelmed with all sorts of things for technical types of hobbies, and any part or material for a future model can be purchased. But many of them can be bought right near your home or made yourself from scrap items or even trash.

I’ll start with the main, so to speak, material from which many aircraft models are made - these are ceiling tiles, depron (a substrate for laminate) and penoplex (orange insulation). Perhaps, besides electronics, these are the only materials that you will have to specially buy in a store (unless, of course, they are lying around somewhere after the repair).

Ceiling tiles Sold at any repair store. Tile thickness - 4 mm. It is worth noting that ceiling tiles vary in both shape and density. This should be taken into account when choosing, because some of its types bend very well along the fibers, and some are so rigid that it is better to cut out rigid structural elements (ribs, frames) from them. In addition, there are tiles in the form of squares 50 by 50 cm, and sometimes in the form of rectangles 20 by 100 cm. The second option is well suited for the manufacture of fuselages, so that the same sidewalls are solid.

Of course, it is better to choose a tile that is white, without embossing or patterns, plain so that its design does not show through the tape and paint, and smooth, without unevenness on the reverse side.

Depron(underlay for laminate) - sold in flooring stores, usually in plates 50 by 100 cm, 10 pieces per package. Thickness - 3 mm (but sometimes thin, about 1.5 mm). One such package is enough to produce 4-5 models with a wingspan of about a meter. The color, as in the case of ceiling tiles, is better to choose a lighter color, otherwise the pen marks will not be visible, and without corrugation.

Penoplex- sold in construction stores in plates 50 by 100 cm. Thickness - 25-50 mm. This material varies in density and hardness. Some types can be crushed with your fingers, some are hard as a board.

This material less commonly used in model making entry level, but then it’s difficult to do without it. Since it can be easily processed with a knife and sandpaper, almost any shape can be cut from it. After processing the foam part, its surface can be primed with PVA glue, painted and varnished, after which the part (or the entire model) looks like it was purchased.

Plywood for modeling you need thin (2-3 mm) and light, which causes some difficulties in finding it in ordinary construction stores. The best source of such plywood is wooden fruit boxes, for which it is nicknamed “orange”.

In any supermarket, such boxes contain various overseas fruits, and the boxes themselves are often thrown away after the products are sold. You can approach the store employees and ask for a couple of boxes. One box, if used wisely, is enough for half a dozen models.

Reiki short lengths can also be obtained from fruit boxes, but not from plywood, but from those knocked together from thin planks. Such a board can be sawn with a saw or even with an ordinary jigsaw into thin (and very light!) slats, which are always useful for strengthening the structure of the airplane.

In addition, slats can be sawed from ordinary wooden rulers, which are sold in office supply stores. They are most often used to make wing spar.

Even in modeling, a tree such as bamboo- in the form of bamboo skewers, toothpicks and sushi sticks. Thin bamboo skewers bend well over the flame of a burner or stove, which makes it possible to make frames from them various shapes. In their direct form, they are convenient to use as rods for control surfaces and as struts for wings and tail surfaces.

Sushi chopsticks Well suited for the manufacture of landing gear struts or in the manufacture of a motor mount frame.

If you need very long bamboo sticks, you can look in the attic for a bamboo mat or blinds that have sticks up to a meter long.

And to make indoor (very light) models, you can use thin bamboo sticks from a small table mat.

In some cases you can also use ice cream sticks, for example, as a synchronizer for the elevator halves.

Tin cans from canned food and drinks - a source of light and thin tin, which can be easily cut with scissors and soldered without much effort. For example, the bases of a wire chassis are made from it.

Or they use tin corners (as well as threads with glue) to connect wooden frame elements.

Bicycle spokes- very good and durable steel wire. They can be used to solder chassis struts for small models.

For larger models, it is better to buy everything for welding in stores. electrodes or welding wire the required diameter.

The electrodes can also be used in the manufacture of a table for radio control equipment, after first knocking off all the powder from them.

In addition, for such a table it will be useful shoulder strap from an old sports bag.

In many Russian dachas there are non-working refrigerators, inside of which there could easily be tray made of thin duralumin. This is an ideal material for making landing gear for a small aerobatic model.

However, such a stand can be bent from a piece joining tape for linoleum.

You also don’t have to buy the wheels for the model, but make them yourself. For example, from foam rubber And plastic cards.

Foam rubber is easy to find in tablet packaging or take part of a travel mat. Can tell you more about this.

But instead of foam rubber you can use cork mats(there is even a cork backing for laminate), although this is a rarer option.

When working with ceiling tiles, you often need clamps to secure, for example, a sealed wing edge. There are a lot of different clamps on sale, but when creating a model, up to a dozen of them are required, which results in a rather impressive amount. The most ordinary ones will come to replace them clothespins And hanger clips.

Clothespins are more suitable for gluing wooden parts or some internal parts from the ceiling, because very noticeable marks remain on the surface of this ceiling. Clips from hangers do not have such a strong spring and are sometimes covered with soft silicone inside, as a result of which they leave less noticeable marks. But, if necessary, you can place rulers or plastic cards under the clamps, then there will be no traces of them left at all.

Plastic bottles in modeling, these are primarily the lights and hoods of aircraft models, which are made using the so-called “bottle” technology. That is, by shrinking a bottle on a wooden block. Although there are models made almost entirely from bottles.

A wooden block, by the way, can be replaced with a block made of foam block. This material is very easy to process; you can saw it with a regular hacksaw, and sanding it with sandpaper is even easier than wood. And the result is the same.

In some cases, you can use it as an engine hood bottle caps with various household chemicals.

Of course, when making hoods and lights, one cannot ignore nylon tights. If it is not possible to make a hood by shrinking a bottle, you can make a block out of penoplex and form a hood from tights using epoxy glue.

There is also information about this.

Thin plastic, bottle type, for example from various packaging, can be used as an imitation of glass in the cockpit of an aircraft model or as hinges for control surfaces.

At all, hinges in aircraft modeling- this is the same creative process, because they can be done in several ways:

Made of tin and wire

From threads and rulers

Made from plastic and staples

From scotch tape

Instead of purchased locks for hatch covers, you can also use homemade ones made from slats, bamboo and springs from a ballpoint pen.

Or use to fix the lid magnets from the badge.

However, there is also information about the manufacture of various locks.

Homemade hogs for steering surfaces can be made from construction corner.

It is convenient primarily because after gluing the hog does not need to be further reinforced in the steering surface - just bending it with reverse side.

If there is no corner, you can make a hog from plastic card or harder plastic from some packaging. Or from the old one CD.

But such a boar needs to be secured with an additional piece of wire or a paper clip on the back side, otherwise it will be pulled out very quickly.

Purchased rod and wheel clamps can also be replaced with homemade ones, using ordinary terminal blocks. In many ways, they are even more convenient, since to fix them you do not need a thin and rare hexagon, a simple screwdriver is enough.

Steering surface rods can be made from steel wire entirely, or from the same bamboo skewers, to which pieces of steel wire are tied at the ends with threads and glue.

Can be used as bowdens ballpoint pen refills or cotton swabs, if the rods are made of wire.

For bamboo stick pulls, bowdens can be made from cocktail straws or from balloon sticks.

It is better to glue bowdens with five-minute epoxy glue.

Now let's turn to such an inexhaustible (in terms of spare parts for modeling) part of modern life as personal computer , aka RS.

Old CD-DVD drive from a computer is a whole Klondike for a modeler.

First of all, it has one or two guides for heads with a diameter of 3 mm. They are ideal for replacing a bent motor shaft, for example.

Secondly, the laser head itself has strong neodymium magnets, which can be used in the hatch cover of an aircraft model to quickly close it.

Thirdly, directly engine The drive can be rewound and used for its intended purpose on model aircraft with a pusher propeller. There is information on how to rewind an engine, but here is how to remake an engine for the needs of aircraft modeling (and there are even videos on YouTube).

In addition, the drive will come in handy rubber washers(under the engine base, for example, to dampen vibrations) and various bolts and screws, which can be used to fix various elements in models.

If necessary, even yourself frame drives can be used to produce thin but strong metal plates.

Computer cables from now unused floppy drives or from IDE hard drives are great for making servo drive extensions.

If the length of the cable is not enough, you can use wires from network cable (twisted pair), there are 8 wires there.

Four-pin power connectors, or rather the contacts from them, can be used to connect the wires of the engine and the regulator, the main thing is to tighten them into heat-shrinkable tubes. However, they themselves wires Can also be used for motor and governor.

If the motor shaft on a larger model is bent, for example, a shaft with a diameter of 5 mm, then you can use drill tail or screwdriver rod. But it is recommended to carefully measure the screwdriver with a caliper, because they have a fairly large error.

Purchased rubber bands for prosavers can be easily replaced rings from the necks of balloons, or take rubber bands for money.

In general, rubber bands They are also used for hatch covers and even for connecting wing consoles in some models.

For diluting epoxy glue in small quantities it is convenient to use caps from jars of baby food. If you have children, quite a lot of these caps accumulate, and it’s not a shame to throw them away after a single use.

For large volumes epoxy (when making a hood from tights, for example) is better to use plastic cups.

To secure the battery, regulator, etc. inside the model, special straps with Velcro are sold. But instead of such Velcro you can use ski straps(sold in sports stores) or Velcro from power cables laptops and other portable equipment.

Now let's touch on such things as tools and other materials that are used in modeling.

To begin with - adhesives:

1. Ceiling adhesive.

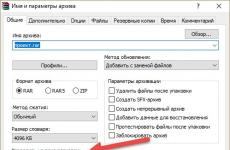

Sold in fairly large bottles, but for convenience it is better to pour it into a 20 cc bottle syringe(first, for safety, break off the needle). There is no point in focusing on names; all adhesives for ceilings are for the most part the same.

2. PVA glue.

The best glue for gluing wooden frame parts. A more liquid version (or diluted) is used for priming finished models or their parts.

3. Epoxy glue.

Need as ordinary epoxy two-component glue - for the manufacture of hoods and lights from tights, and five-minute- for quick gluing of different parts of the model. There is also glue just a minute, but it can only be used together with a standard mixer attachment; on the lid (when stirred with a match) it hardens faster than it can be stirred well.

4. Super glue.

It is used a little less often when working with the ceiling, because it mercilessly dissolves it, but it is often used in balsa models.

Multi-colored tape.

It is sold in many stationery stores, but does not offer a wide variety of colors. I have only seen white, black, red, blue, cyan, green, yellow and orange. There is also gray reinforced (convenient for strengthening the leading edge of the wing) and transparent.

All other variations are some kind of special striped tape and so on.

To work with tape (and model film too) you will need a special model iron to attach this tape to the ceiling tiles or depron.

But such an iron is quite expensive, and therefore it can be easily replaced with an ordinary iron, but first you need to practice well and empirically select the desired temperature, so as not to wipe off the remains of melted tape from it later. In the future, if you are very interested in the hobby, you can buy a small iron on sale in a supermarket or even splurge on a model iron, but this is everyone’s personal choice.

In addition, it is very useful for cutting colored tape into narrow strips (and even for cutting out some designs). self-adhesive film base. You can stick tape on it, and then use scissors and a cutter to cut out almost any design or cut the tape into thin stripes. The adhesive tape from such a base peels off very well and does not lose its properties, and the resulting application can be easily transferred to the model.

An example of a drawing made from black tape.

If for some reason it is impossible to work with tape, the model can be painted acrylic paints. But there are some subtleties here too.

Firstly, light-colored paints do not always cover pen marks on the ceiling, which affects the appearance of the model.

Secondly, acrylic paints in cans can dissolve ceiling and depron, since they contain a substance that reacts with foam, and therefore you need to use paint in tubes or cans, and apply it with a brush or swab.

Thirdly, this paint dissolves in water, and therefore it is advisable to cover the model after painting varnish(preferably acrylic).

It is worth noting that tape, unlike paint, still significantly adds strength to ceiling models, which is important for novice pilots and in cold weather, when the ceiling becomes more fragile.

But a painted model looks neater and brighter, and a beautiful model, as we know, flies beautifully.

You may still need purchased tools hot glue gun. With its help, it is convenient to fix servos in the model and grab the wires so that they get in the way less.

The only thing you shouldn’t glue with it is the ceiling itself (this has happened!), because hot-melt adhesive is very heavy, and its remains in the form of, excuse me, snot, make appearance The models are very ugly.

In addition, in modeling you may need more than once dremel or micro drill. Supermarkets sell very inexpensive models that even work from a car's cigarette lighter, which allows you to use it even in the field. The kit usually comes with a large number of various attachments for grinding, polishing, drilling, expanding holes, and even a micro-grinder. But in cheap models, it’s worth noting right away that the drills are useless, you can even bend them on wood. But everything else is not very poor quality.

Some modellers make something like a Dremel from a regular aircraft model engine, but the question of finding attachments remains open, and therefore such a Dremel is of little use.

Of course, in addition to everything I listed above, there are about two dozen more tools that modelers of all levels need (soldering iron, screwdrivers, screwdriver, pliers, vice, etc.), but I don’t see the point in listing them all, because they are more obvious.

This is where I would like to end this article, and for a little relaxation I suggest watching a short video of the flights of a two-meter model made of depron and adhesive tape. Yes, yes, even a model of this size can be made from such simple materials.

This article describes detailed process making a hood for an aircraft model from nylon tights and epoxy glue. Many people have old tights, but if you are a convinced bachelor and don’t wear tights, then you can buy any at the supermarket.

I would like to warn you right away - the process of making one hood or canopy may take several days, since the epoxy takes quite a long time to dry. In my opinion, it is better to start the cowl and canopy at the initial stage of fuselage production, rather than at the end of the model's construction.

And one more small note (my own experience): it is better to work with epoxy in a warm and dry room. When I made the hood in the rain on a cold balcony, the epoxy absorbed so much moisture that it did not dry for almost a week. I had to warm up the hood in the oven.

Materials:

- Penoplex

- Ceiling tiles

- Nylon tights

- Epoxy glue (not fast-curing)

- Ceiling glue

Tools:

- Sharp stationery knife

- Disc marker

- Sandpaper

- Square

- Wand

- Plastic cards

- Wire

- Glass or jar

- Minidrill

Step 1. Drawing templates

We draw the nose part, the engine and the spinner on cardboard, not forgetting the thickness of the fuselage skin, and draw out the shape of the hood in three projections.

Cut out the templates. A circle with a diameter slightly larger than the base of the spinner is needed to give a more streamlined shape to the hood and to more easily determine the location of the future hole.

Step 2. Gluing the workpiece

On a sheet of penoplex we mark rectangles slightly larger than the template. The number of rectangles directly depends on the size of the future hood.

We glue them into a large block with ceiling glue. Since penoplex is smoother and does not absorb glue, I recommend letting the coated parts dry first.

Step 3. Cutting out the blank

We draw the contours of the future hood on the finished block according to the template. Then we draw perpendiculars along the square to more accurately draw the contours on the back side.

We draw the side contours in the same way.

Using a sharp utility knife, cut out the side profile and draw a line (axis of symmetry).

We apply a template along this axis, draw the contours and, based on the contours on the other side of the blank, cut out the front profile.

We cut out the third profile and glue a circle from the ceiling.

We process the block with sandpaper to obtain a smooth surface.

Step 4. “Epoxy” work

We wrap the blockhead in a plastic bag (to make it easier to remove the finished hood later) and pull tights over it in one layer.

We twist the bottom of the tights so that all the folds go away, secure them with wire and glue two blocks of foam foam onto the ceiling glue, so that later the blockhead can be placed evenly.

We dilute epoxy in a glass and begin to coat the blockhead with it using a plastic card.

The process is not quick, because in good lighting you need to make sure that the epoxy saturates the tights evenly and does not cause strong smudges in the lower part. Once the block is completely coated with epoxy, it can be placed on a cabinet to dry.

After the epoxy has dried, we cut off the excess tights from the bottom and tear off the penoplex bars.

We can start Step 4 first, but the package is no longer needed. For normal strength, you need at least three layers of tights, that is Step 4 must be done three times.

Step 5: Final Steps

After the third layer of epoxy dries, we get a very strong and smooth hood.

Now all that remains is to remove the blockhead. To do this, draw a line along the bottom edge with a marker and use a mini drill (if you don’t have such a tool, you can use a hacksaw or a needle file) cut off the excess along it. The work is very dusty, so I advise you to use protective equipment (respirator and goggles).

Cut a hole for the motor.

We squeeze the block through the hole and separate the film in which it was wrapped from the hood.

Quite often modelers are faced with a very unpleasant moment. Need to make a new onecabin glazing (flashlight).

Since the one in the set is either lost, broken or cracked, or is of the wrong shape or of poor quality. Manufacturinglantern, and indeed transparent elements of the model, is a rather important moment. Since transparent parts cannot be puttied or built up if they are not manufactured accurately. The part must be done immediately and as accurately as possible. There are several ways to make lanterns. I want to focus on the classic, time-tested more than once. Pullcabin glazing made of plexiglass using a punch and a matrix. First we make a matrix, exactly along the contour of the cabin. You can make a small margin of 0.1-0.2 mm for subsequent adjustment, cleaning and polishing. For this I use pieces of getinax, fiberglass or something similar.

Afterwards, from a type of wood, such as beech, so that there are no fibers and it is quite hard, we make a punch. Moreover, all punch dimensions must be reduced by thickness cabin glazing. But it’s better to increase the height a little so that the lower edge of the lantern is above the plane of the matrix when the punch is inserted into it. It is also better to mark on the punch, for example with a pencil, the lower edge of the lantern plus a small margin for cutting.

For large scales, 1mm thick plexiglass may be suitable, but for something like 1:72, you need to look for something much thinner or reduce the thickness yourself.

By the way, thickness is one of the reasons why some companies, especially when producing models using LND technology, for the manufacture cabin glazing films are used. Nowadays, from a huge number of packages, you can select a blank of the required thickness. Personally, for a number of reasons, I don’t like these films, and I use plexiglass to make lanterns. But let's return to our manufacturing process. To reduce the thickness, I grind down one of the sides of the workpiece to the required thickness on a piece of sandpaper. Usually new plexiglass is protected with film on both sides. Therefore, we remove it on one side and leave the other side alone for now, so as not to scratch it during the grinding process.

After obtaining the required thickness of 0.5-0.6 mm, remove the film. If necessary, if you want to make the lantern open, it can be made thinner. The side on which the film was placed will be the inner side, as it is smooth and without scratches. Now, near the heat source, where we will heat the workpiece, for ease of work, you can make something like this kind of slipway.

Then we move on to the pulling process itself. cabin glazing. To do this, the plexiglass blank, held with tweezers or something similar, must be heated until it begins to bend easily under its own weight. It is better to heat over an electric stove or over a gas stove so that the plexiglass does not fall into the flame, but is heated above it. After heating, you need to very quickly place the workpiece with the polished side on the matrix and press on the smooth side with a punch.

You may not succeed the first time. Therefore, another advantage of plexiglass is that it can be heated again and it will take its original shape. Then you can try again. Of course, this cannot be done indefinitely. After obtaining the desired result, hold the punch for several seconds until the plexiglass cools completely. Then we remove the workpiece from the matrix and carefully begin to cut out the lantern.

If you have previously marked the punch, then along the marking lines, using a file, for example from a blade or a special one, we cut out the desired part.

Then we adjust the lantern in place. Since the outer side was not processed after grinding, now you can slightly adjust the lantern to its shape. If necessary, sharpen the edges, because during the drawing process, sharp edges collapse. Then we clean the lantern with waterproof sandpaper of different grits. Afterwards we polish it with GOI paste. I’ll say right away that this process is not easy, but after training you can get parts of excellent quality.

This article shows the manufacturing process cabin glazing made of plexiglass for the LaGG-3 aircraft manufactured by Roden on a scale of 1:72. This is what the lantern ended up looking like. And this is how it looks on the model.

About dummies, matrices and lanterns

or Street of Plaster Lanterns

This article was originally dedicated to my own successful project- Kamikace Compact. By that time, I had already mastered making a lantern (on the Phoenix Bird project), but alas, I could not capture the process in photographs (everything was spontaneous, by trial and error), therefore, when making a dummy and a lantern, respectively, for Kamik, I captured the process in detail.

I make lanterns exclusively from PET bottles. Beer houses or shops that sell kvass. At least 2-3 liters and preferably brown. In extreme cases, you can do transparent ones, but then you will have to paint the inside with car paint from a can (a little bit to fog up in the light) because a completely transparent canopy on an airplane is pornography and it is not visible in the sky at all.

Styrofoam dummy

The lantern, according to the technology of gypsum products, begins with a foam block.

It is not ball or similar granular that is used, but red Penoplex or blue foam, used in electric aircraft. Penoplex is preferably the densest one available. Using 30mm plates we create a prototype of a dummy. The height is 70mm according to the drawings, so we glue 2 pieces together and glue the bag on top of the 10mm thick stubs. You can glue it on thick Henkel PVA or on Titan. On Titan the bag dries for three hours, on PVA overnight.

I advise you to have a cutting string for foam plastic - it helps a lot! However, you can use a knife to cut a 10mm (preferably with a margin) plate.

The tools used to make the primary block are a construction blade knife, coarse sandpaper, thinner sandpaper, and a very useful thing - both types of sandpaper glued to 2 sides of the plywood. It turns out to be a very convenient file. I mainly use it in sanding the blockhead.

I immediately advise you to make the blank blank longer than the cockpit plateau. 10-20 mm longer. This is necessary in order to then properly trim the edges of the stretched bottle and cut off possible folds (I’ll talk about this below).

First, we cut off the scraps from the blockhead, bringing its future appearance closer to the required shape. I’ll say right away that I make lanterns by eye. I don’t do anything exactly along the side profile. It is best to have a drawing in front of your eyes and approximately reproduce its shape. This will make it easier and there will be fewer mistakes and mistakes.

We stupidly cut off the layers of foam and get this blank:

The main part of the work is done with a plywood “file” and coarse sandpaper. Movements are circular and along the lantern. We try not to lift the foam. When more or less a shape is formed, we finish it with the other side of the “file” with finer sandpaper.

If you can’t get to it with a “file,” then take a piece of sandpaper (“flexible”) in your hands and, pressing it with your finger, carefully process the desired area. I had one like this at the transition of the forehead of the canopy into the edging repeating the shape of the cabin lid.

We constantly try on the bobblehead to the fuse to achieve the closest possible shape to the front part and especially to the gargrot.

At the end of all sandpaper work, we go over the entire surface with “thin flexible” sandpaper in order to smooth the surface as much as possible. As a result, we get something like this:

I always make these add-ons from scraps:

I glue the add-ons using droplets of slow cyacrine with an activator.

Preparing for casting

Well, here comes the most difficult part of the lantern making operation and at the same time the dirtiest.

At the hardware store I bought a painting bucket with a handle and a basin for something childish.

A 6 or 8 liter bucket (I don’t remember) will serve as a container for the matrix. The bucket is rectangular with a slight taper. A very good purchase for 95 rubles!

This is what the foundry looks like when it is 100% ready:

We glue the blockhead using Titan glue to a piece of cardboard that is the same size as the flat part of the bottom of the bucket. First, we put a 50-liter trash bag in a bucket and put a block of cardboard in it (you can see it in the photo). The cardboard straightens the circumferential bottom space around the blockhead and prevents it from floating in the solution (this has happened).

We dilute alabaster in a basin. Important note!!! You need to understand that you can’t fill the matrix all at once; as a rule, you won’t calculate the volume of the solution and it will probably turn out thick. Therefore, as a rule, I fill it in 2-3 batches.

In this case, the solution needs to be liquid. The consistency is approximately the same as liquid sour cream or yogurt:

Casting technology

First, we pour water into a basin and pour alabaster into it (I use a glass made from a bottle), constantly stirring with a stick. Cooks roughly imagine the process. When you get the desired consistency (not water or thickness, but liquid sour cream), without waiting for anything, we begin to pour it into the bucket. First we pour over the block itself, and then we form the walls of the matrix. This is very important. In the first step, we make some kind of shell around the blockhead, and in the second we modify the walls to a large thickness (which is determined by the size of the bucket and the blockhead itself). As a rule, during the breeding of the second pass, the first one has already solidified. Remember - alabaster hardens very quickly!

The height of the fill cap above the crown of the blockhead is at least 2 cm. This will be the thickness of the bottom of the matrix.

This is what the fill looks like immediately after the second pass:

Let it dry for about an hour, pull the matrix out of the bucket by the bag and remove the bag and cardboard. Our fool is exposed:

Much later, the idea came up - when pouring the matrix, put certain elements - stress concentrators - into the space between the block and the walls of the bucket. Let's place the strips of cardboard vertically, placing them flat and diagonal to the center. Then it will be easier to break them, because they violate the integrity of the matrix mass.

As a rule, it is not possible to pull out the blockhead intact, so it must be etched out. There is no need to completely etch out the foam - you just need to help it come out on its own. We take acetone and pour it along the edges of the blockhead to etch its surface. Using a screwdriver or something like that, we try to pull out the blockhead. As a rule, it rests somewhere there, so we add acetone around the edges and touch up the necessary places. In the end, he crawls out with a smack, leaving a puddle of melted water. We carefully pull out this kaka, if something remains on the walls of the matrix, under no circumstances do we pick it! Let it dry a little. The acetone evaporates and the fused foam hardens. Then carefully remove it in the form of a crust.

Unfortunately, I didn’t take a photo of the stage of filling the blockhead, so I’ll describe it in words. The separating layer can be used in different ways. For the Phoenix Bird lantern I used the same trash bag, but then there will be inevitable wrinkles. Therefore, we make a mixture of soap and use a brush to lubricate the matrix inside. After drying, a film is obtained. We put 2 layers of porridge, since the first one will absorb the plaster.

This time I used a different separator - vegetable oil. Overall not bad either, but much worse than soap.

The solution for the blockhead needs to be made a little thinner. This is extremely important! If you leave the solution in a basin, then the quality of the block will not be up to par and it will need puttying. Which is exactly what I had this time. :-(

After pouring the solution, wait for three hours and very carefully break the matrix. Using a chisel and hammer, we first try to chop off the end walls and then very carefully make a shallow groove at the bottom of the matrix (where the crown of the blockhead is located). Thus, the matrix will fall apart along this stress line. Next, by gently hitting the walls of the matrix with a hammer and chisel, we try to split the matrix in two (preferably by chopping off pieces from the walls). As a result, we get a seed:

Due to laxity, this blockhead had to be puttied with a very liquid alabaster solution and then actively sanded. Ideally, you get a relatively smooth block, which then needs minimal sanding.

Wrapping process

I also didn’t film the wrapping process (I had no free hands), so I’ll also describe it in words. We cut the pre-selected bottle around the bottom at its base. The bottle should preferably be cylindrical, without any narrowing in the middle or embossed patterns. In general, the bottle should be as smooth as possible. I found a cool bottle of kvass (back in the summer, when there was a lot of this stuff).

We put the blockhead into the bottle so that the neck of the bottle hits the front end of the blockhead and slightly below (the blockhead in the bottle will be slightly skewed). We insert pieces of wood into the space between the wall of the bottle and the bottom of the block to reduce the volume of the tightening (the bottle does not tighten indefinitely!).

Using a construction hairdryer, we first “close” the bottle, that is, we heat the “skirt” of the resulting structure so that the edges of the bottle are wrapped around the back of the block (this is so that the block does not squeeze out of the bottle when tightening the main part of the surface). And we try to warm the blockhead first from above, and then from below. This is to prevent wrinkles from forming (for me it turned out at the very top).

Next, we heat the main part, pulling the entire space of the bottle onto the block. The temperature of the hair dryer is not at maximum (my hair dryer heats with two temperatures - 300 and 600 ° C), but at medium (I heated at 300). The bottle may begin to melt if heated to the maximum.

In general, after smoothing the bottle as much as possible on the block, we cut off the ends of the bottle, cut off the turn at the back end and the neck at the front, and also cut the bottle from the bottom. We remove the lantern from the blockhead and here is the intermediate result!

Final photos of the result:

Alexander Niskorodnov (NailMan)

How to do it at home and with minimal costs make a cockpit canopy?

I thought that this topic had not been relevant for a long time, but if you take into account the number of questions received, I understand that I got excited. Therefore, I decided to devote a separate article to how I make lanterns on a model from a plastic bottle. What is pleasing about this process is that business is combined with pleasure. And the costs are really minimal and come down to the cost of the drink, the plastic bottle from which will be used as a material. I don’t know about anyone, but for some reason I like lanterns made from beer bottles the most. However, let's get down to business...

Actually there is not so much to do, you need to make a blank. To do this, we take a block, I used linden, it is more uniform and easier to process. First we process the side surfaces to obtain the desired shape of the bottom surface. Dimensions can be taken from the drawing, from the top view, or by directly measuring the fuselage. It should look like a trapezoid. Then, on a piece of whatman paper or cardboard, I copy the profile of the future booth from the drawing and make a pattern. I use it to mark the blank with an allowance along the length and bottom:

After this, naturally, the top of the blank is processed along the contour. There are many ways, first you can do this:

and then like this:

After 20-30 minutes you get something like this:

We apply markings to the ends of the workpiece:

,

,

I copied the contours directly from the fuselage onto the same Whatman paper and made patterns.

After this, I pre-processed the back of the blank:

,

,

Then he tore off the front:

Now all that remains is to refine our clumsy (in the literal sense of the word) work and give it a finished look. 20 minutes of sanding and we get a cool blank:

Now you will have to put your work aside for a while and rest a little, especially since this is simply necessary to continue working.

Having assessed visually (and maybe even instrumentally) the dimensions of our blank, we head to the store, where the largest possible range of drinks in large plastic packaging is presented. I don’t know why, but I prefer brown-tinted booths, so I was “forced” to look for a lantern blank in the beer section. The 2.5 liter bottle of Bolshaya Kruzhka beer was almost perfect in both form and content. Having used the contents of the workpiece for its intended purpose, carefully cut off the bottom and stuff the blank into it. To avoid having to shrink the plastic a lot, we somehow fix the blank inside the workpiece.